“We're here! This is free Wednesday, and that means you don't have to pay anything (but you don't get Mondays and Fridays - which are really great).

And we're just trying to give away a bunch of stuff on Wednesdays. Some of it's going to be goofy, like pencils with erasers that I bite when I'm writing.

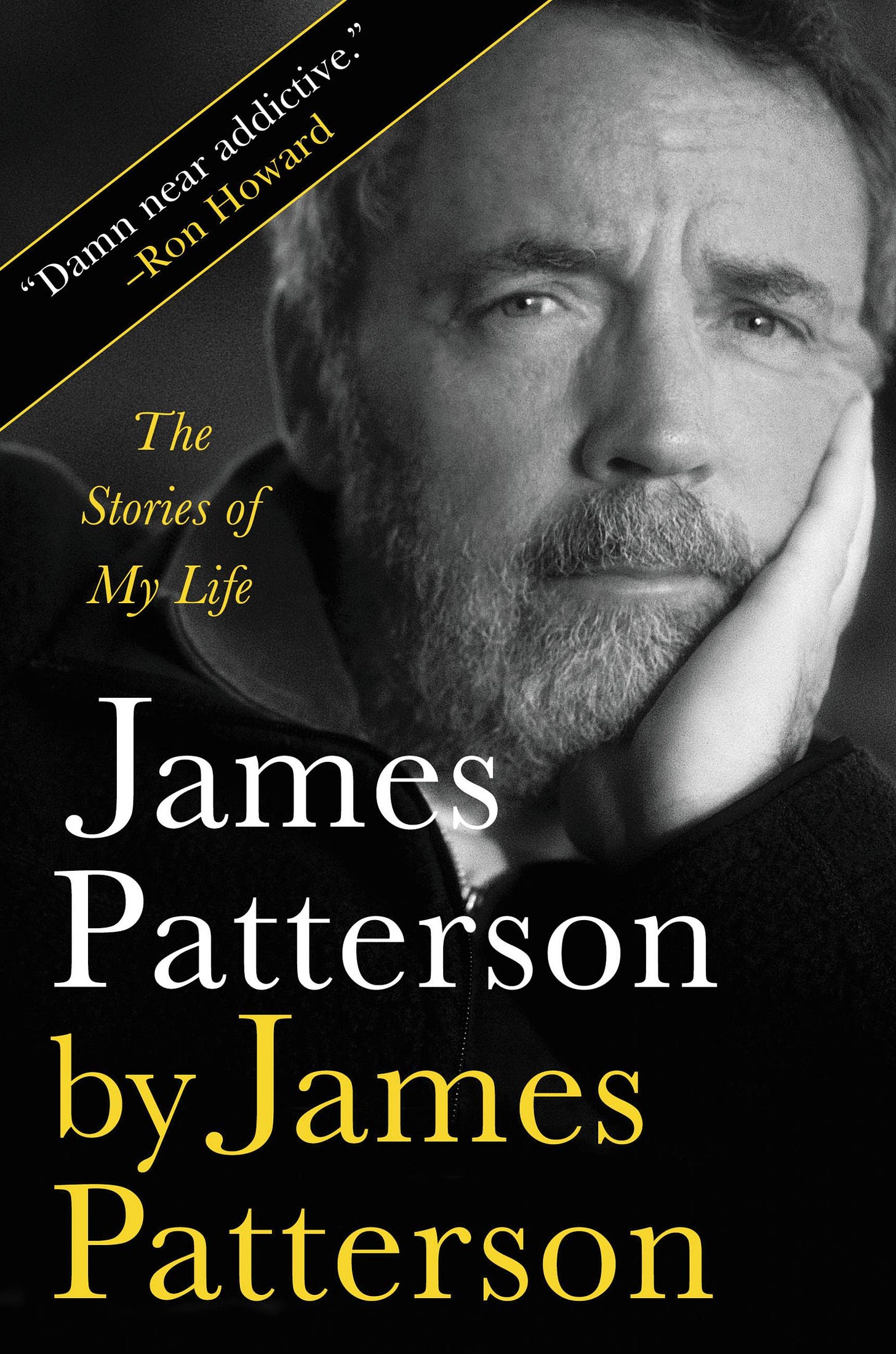

I want to talk about my autobiography, James Patterson by James Patterson, which is the whole title. Over the course of, I don't know, a couple of months or whatever the heck, we'll give away all the chapters to that. We'll give away chapters to other books that haven't been published yet. We'll try to make it interesting.

I think my autobiography is actually my best book. My first book, The Thomas Berryman Number, won an Edgar as Best First Mystery when I was 26 and the autobiography, I obviously published when I was a lot older, and there's proof that I totally wasted my talent as a writer doing all those thrillers. But so be it.

I started the autobiography during COVID. I had nothing better to do. So I just started writing story after story. And just to give you kind of a sampling, I worked my way through college at McLean Hospital. I was an aide there, and it was just fascinating. It woke me up. I was sort of a small town kid, and all of a sudden, I'm dealing with a lot of people that had money or, you know, they were crazy in good ways.

And James Taylor, the singer, was there. He wasn't famous yet, and he used to sing in the in the coffee shop, and I could be 15 feet away from him, and he's singing “Sweet Baby James” and and “Fire and Rain” and stuff like that, which he'd already written. So that was exciting and interesting. Robert Lowell, the poet. He came in several times, and there was one other English student who was an aide, and we used to go in there, and Lowell would not just read his poetry to us, but explain what he had in mind.

Early on, when I was 26 or 27, I went to my first sort of literary party in New York City. It was at an agent's house, and there was a lot of noise going on. So I sort of wandered back through this hallway, and there was a bedroom, and it was packed with this sort of literary mob. And in the middle of the room there were these two little men, James Baldwin and Norman Mailer, and they both had their fists clenched and they were arguing about who was a better writer. And I just found it hilarious. That's one of the reasons I sort of laugh when I think about these various little things that writers get into in terms of who's better, who's worse, or whatever that is. So I learned to smile at that stuff in general. And I don't think this is stupid, but I tend to laugh at stuff. I'd rather laugh than cry at things that happen in the world.

Early on, before I published The Thomas Berryman Number, I got turned turned down by 31 publishers. To this day, there are still some editors around who turned my book down and they send me stuff for blurbs - and I'll blurb them anyway. But it could be out of revenge.

Then there are some family stories. But once again, they're all stories.

My father was just about to go off to World War II, and he got this call from this guy. He introduced himself as George Hazelton, from a nearby town, about 20 miles from where I grew up in Newburgh, New York. And this guy, George Hazelton, he told my father that last night, after dinner, his parents took him downstairs, and they said, “George, you know we love you so much, but we have to tell you, because you're going off to war, that we adopted you. You're not our natural son.” And then George Hazelton, over the phone, told my father, he said, “I'm your brother.” So that's how my father found out that he had a brother.

So there are little stories like that. Later on, my father and his brother both survived the war, and my uncle called again. He said, “I found our father.” Neither one of them had ever met him, at least not once they were older than one or two years old. And my uncle said, “I'm going up to see him.” He's a bartender in this crummy little bar in Poughkeepsie near the bridge. And my father said, “I'm not going to go see the bastard.” So my uncle went up by himself. My uncle was a very sweet, nice man, and he wasn't a drinker. So he got to this bar. And there’s this guy behind the bar, this Irish guy, (and to this day I don't know my grandfather's first name). So, my uncle is watching this guy, and after 20 minutes, he leaves without ever introducing himself to his father.

Doing my autobiography at this age - it made me a better writer. It really got me to concentrate more on sentences. Some of you out there, some of you writers, think you're better than I am, and maybe you are, maybe you aren't, but you'll read it as the chapters come along, James Patterson by James Patterson, and you’ll come to your own judgment about your own writing and my writing, and that'll be kind of fun.

But anyways, that’s the kind of shit we're going to do on free Wednesdays.”

See below for chapters from James Patterson by James Patterson and a chance to win my used pencils!

James Patterson by James Patterson

“Hungry Dogs Run Faster”

This morning, I got up at quarter to six. Late for me. I made strong coffee and oatmeal with a sprinkle of brown sugar and a touch of cream. I leafed through the New York Times, USA Today, and the Wall Street Journal. Then I took a deep breath and started this ego-biography that you’re reading.

My grandmother once told me, “You’re lucky if you find something in life you like to do. Then it’s a miracle if somebody’ll pay you to do it.” Well, I’m living a miracle. I spend my days, and many nights, writing stories about Alex Cross, the Women’s Murder Club, Maximum Ride, the Kennedys, John Lennon, young Muhammad Ali, and now this.

My writing style is colloquial, which is the way we talk to one another, right? Some might disagree — some vehemently disagree — but I think colloquial storytelling is a valid form of expression. If you wrote down your favorite story to tell, there might not be any great sentences, but it still could be outstanding. Try it out. Write down a good story you tell friends — maybe starting with the line “Stop me if I’ve told you this one before” — and see how it looks on paper.

A word about my office. Come in. Look around. A well-worn, hopelessly cluttered writing table sits at the center, surrounded by shelves filled to the brim with my favorite books, which I dip into all the time.

At the base of the bookshelves are counters. Today, there are thirty-one of my manuscripts on these surfaces. Every time journalists come to my office and see the thirty or so manuscripts in progress, they mutter something like “I had no idea.” Right. I had no idea how crazy you are, James.

I got infamous writing mysteries, so here’s the big mystery plot for this book: How did a shy, introspective kid from a struggling upstate New York river town who didn’t have a lot of guidance or role models go on to become, at thirty-eight, CEO of the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson North America? How did this same person become the bestselling writer in the world? That’s just not possible.

But it happened. In part because of something else my grandmother preached early and often — hungry dogs run faster.

And, boy, was I hungry.

One thing that I’ve learned and taken to heart about writing books or even delivering a good speech is to tell stories. Story after story after story. That’s what got me here, so that’s what I’m going to do. Let’s see where storytelling takes us. This is just a fleeting thought, but try not to skim too much. If you do, it’s the damn writer’s fault. But I have a hunch there’s something here that’s worth a few hours. It has to do with the craft of storytelling.

One other thing. When I write, I pretend there’s someone sitting across from me — and I don’t want that person to get up until I’m finished with the story.

Right now, that person is you.

“Five Years at a Cuckoo’s Nest”

My writing career unofficially began at McLean Hospital, the psychiatric affiliate of Harvard Medical School in Belmont, Massachusetts. It was the summer of 1965 and I was eighteen. Fresh out of high school. I needed a job, any job, and McLean was hiring. I spent a good part of the next five years at this mental hospital. That’s where everything changed about how I saw the world and probably how I saw myself.

I wasn’t a patient. I swear. Not that I have anything but the highest regard for mental patients. I just wasn’t one of them. Besides, back then I couldn’t have afforded a room at McLean, not even space in a double room.

I was a psych aide. I think I was hired because I have empathy for people. You’ll be the judge of that. The heart of the job was to talk to patients and, more important, to listen to them. Occasionally, patients tried to hurt themselves. My job was to try and stop that from happening. In addition to my usual daytime shift, I worked two or three overnight shifts a week, from eleven p.m. until seven in the morning. Most nights I just had to watch people sleep. Which isn’t that easy.

I had never liked coffee, but I started drinking the awful stuff just to make sure I stayed awake, since there were usually patients on suicide watch at Bowditch or East House in the maximum-security wards where I regularly worked. For hour-long stints I had to sit outside their rooms, watching them flop around in bed, listening to them snore, while I fought off sleep at three or four in the morning.

So I had a lot of free time. I started reading like a man possessed during those long, dark nights of other people’s souls.

Two or three times a week, I’d go the three miles or so into Cambridge and make the rounds of the secondhand bookstores. I especially loved tattered, dog-eared books. Books that had been well loved and showed it. The used books cost me a quarter, occasionally a buck, even for thick novels like The Sot-Weed Factor, The Golden Notebook, The Tin Drum.

At the time, I wasn’t interested in genre fiction, the kind of accessible stuff I write. I had no idea what books were on the New York Times bestseller lists. I was a full-blown, know-it-all literary snob — who didn’t really know what the hell he was talking about.

My ideas about how the world was supposed to work had been framed growing up in Newburgh, New York, and the somewhat parochial outer reaches of Orange County. As I read novel after novel, play after play, my view of what was possible in life began to change.

That first summer at McLean Hospital, I read a lot of James Joyce and Gabriel García Márquez, plus as much Henry James as I could stomach. I was into playwrights: Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter, Ionesco, Albee, Israel Horovitz. I read novelists like John Rechy and Jean Genet (Our Lady of the Flowers will get you thinking). Also Jerzy Kosinski and Romain Gary. I loved comedic American novelists. Stanley Elkin and Thomas Berger got me laughing out loud. So did Bruce Jay Friedman. John Cheever. Richard Brautigan. Vonnegut.

But the novel that influenced me most was Evan Connell Jr.’s Mrs. Bridge, the story of an ordinary middle-class family living in Kansas City. Mrs. Bridge is told from the point of view of India Bridge, a wife and mother. A companion novel published ten years later, Mr. Bridge, tells the same story from the point of view of Walter, her curmudgeonly lawyer husband. A reviewer in the New York Times wrote, “Mr. Connell’s novel is written in a series of 117 brief, revealing episodes. The method looks and is rather unusual. . . . It enables any writer who uses it to show, with clarity and compactness, how characters react to representative episodes and circumstances.”

Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge helped inspire my writing style (don’t blame Evan Connell). So did Jerzy Kosinski’s novels Steps and The Painted Bird (don’t blame Kosinski). Short chapters. Tight, concise writing (hopefully). Irony and wit (occasionally).

During the time I worked at McLean Hospital, I read everything (except bestsellers, God forbid) I could get my hands on. Then I started scribbling my own short stories, hundreds of them. That was the beginning of the end. I was now officially an addict. I wanted to write the kind of novel that was read and reread so many times the binding broke and the book literally fell apart, pages scattered in the wind.

I’m still working on that one.

“Change is Good, but Change is Hard”

In the spring of 1999, I asked for a meeting with the brass at Little, Brown. I was selling a lot of books by then, so I got the meeting. The publisher, Larry Kirshbaum, had become a close friend of mine. He still is. We lunch at Patroon, Stuart Woods’s fictional hero Stone Barrington’s favorite eating and drinking spot in New York City.

I’d been writing a mystery novel a year, and the Little, Brown execs had it all programmed on their little spreadsheets. Now I told them I wanted them to consider a change — a big change for the entire publishing business, as it turned out.

I took a breath, then told the Little, Brown elites my idea. “I want to write two, maybe three books a year.” No audible gasps came from the august group, but I detected skepticism and at least one wrinkled brow.

I gave them three ideas for new books. One was for the Alex Cross series, one was a twisty beach mystery called The Beach House, and one was a love story, Suzanne’s Diary for Nicholas.

During the meeting, I told them how the story for Suzanne’s Diary came to be. At that time, my wife, Sue, had already taken about five hundred thousand photographs, maybe a million, of our baby son, Jack. A couple of thick photo albums were sitting on a table in our living room.

One afternoon I started leafing through them. It struck me that at some point, Jack might be looking at the same photo album, but Sue and I would be gone. Then I had a much worse thought. I imagined Sue and I going through the same album — if Jack somehow died before us. That’s how Suzanne’s Diary for Nicholas came to be.

I told the Little, Brown executives the story, and Larry Kirshbaum teared up. His instincts were usually very good. He immediately got the power of Suzanne’s Diary for Nicholas.

Then Larry gave me his thoughts and his decision on the three books. “We love the Alex Cross, of course. And The Beach House sounds fabulous. But Suzanne’s Diary, Jim, that just isn’t your brand.”

That struck me as an interesting comment. I was the one with the big rep for watching over brands like Ford, Burger King, Kodak, and Warner-Lambert. I was pretty sure I understood brands as well as anybody in the room. Or in the building, for that matter. So I wrote Suzanne’s Diary anyway. Little, Brown published it. It became one of my top-selling books ever.

If you haven’t read it, now’s as good a time as any.

Go on, get out of here. Head out to a bookstore. Or go online.

Yeah, you.

In the words of Truman Capote, “A boy has to sell his books.”

JAMES PATTERSON’S USED PENCIL GIVEAWAY!

TO WIN:

Subscribe to HUNGRY DOGS at the button below.

Comment on this post with what you are reading right now.

Share this post