J: There he is. Oh, he's gone. He's coming back. Oh, no, he's there. Hey! how you doing?

K: Good. How are you?

J: I'm doing good. Are you in England?

K: No, I'm I'm in DC.

J: Oh, okay. I was just there over the weekend. I have my US Open tennis hat on for you.

K: Oh, yeah!

J: The one thing I want to warn all the writers who are watching this, this is just a tip for what it's worth…don't ever, ever, ever, ever follow Kwame Alexander in a speaking event. You go first. Don't follow him. Do not do that.

J: So you’re good? Within reason?

K: I’m good! Yeah. How about you? You good?

J: I don't know. I think so…yeah! You know, as far as I can tell. Now, I want to talk about Why Fathers Cry at Night at some point. And poetry. You know, I've been out with Kwame, and watching him with kids and and he'll talk to them for like, half an hour, and then they go, “I'll never read anything but poetry for the rest of my life!”

K: Haha. I love it. I love it.

J: You love it. That's that's the thing. So, let's talk a little bit about that. The beauty of it, the magic, the power, whatever. You know, if you want to, if you don't want to, we'll talk about something else.

K: No, of course, are we just jumping right into it?

J: Oh, yes.

K: Look, I've been writing poetry since I was twelve-years-old. It was unintimidating. There was so much white space on the page, I was like, “Oh, I can get through that…that's easy!” But really, it was just a way to to communicate with girls in college.

J: Oh, yeah. Ha. Oh, that's good. That's how it all starts.

K: I read a lot of Pablo Neruda, and I wasn't very cool, but I could write a love poem, or I thought I could. So it was my way of getting dates, and I ended up getting married because of poetry. So after college, I said, “Okay, this is something I really want to learn how to do, and I want to pursue this as a career.” And of course, I had no idea how to do that, and I was broke for about 20 years, but it kind of worked out okay.

J: Uh huh. Anything that sticks in your brain? Because I love to hear you recite stuff. I'm not going to put you on the spot, but anything?

K: Three things. The first thing. Perform your poetry. Don't just read it. I would go out and perform at churches, at subway stops, bookstores, libraries, wherever I could, farmers markets. I wanted people to hear the words and hear what they sounded like. I felt like if they heard it then and they saw it, then they would see that…okay, this is interesting. This is engaging.

J: Speaking of farmers markets though… was there any effect to you on the sounds you would hear? In terms of rhythm…?

K: The kids laughing, the strollers being pushed…the people in the little boats on the water…I walk through life as a willing participant. I hear and see and I borrow from it all. So absolutely. Absolutely! There was just this sense of community. And that's, I think, one of the other things that poetry does for me, is it allows me to be able to connect with people in an immediate way.

K: And so I think that second thing that I figured out was you got to write something meaningful and significant and relevant. You know, I got to make my personal, your business. The third thing was, I always knew my audience, wherever I was. And if you know your audience you have a plethora of poems to sort of pull from. You'll make those connections that create that community. Ultimately, Jim, I think people buy the books. I think they they get excited about the books, at least for me, because they like me.

J: Really? Haha

K: We like this guy. He's so engaging and interesting. He's a storyteller. I think people want to be around other people who they like.

J: That makes sense. You know, and this is switching a little bit. We both know that this publishing thing is a real roller coaster ride, and for both of us, early on, it was a messy ride. My first novel, The Thomas Berryman Number, was turned down by 31 publishers. It then won an Edgar as the Best First Mystery and The Crossover which won a Newbery - that was turned down by a batch too, right?

K: 23 publishers turned it down.

J: I got you there - 31 to 23.

K: You got me!

J: Yeah, so talk about that a little bit.

K: So that was 2008 when I wrote it, and between 2008 and 2013 you're talking about 23 rejections, and even a rejection from my agent. The messed up thing, is that my agent told me he sent the book out, and over the course of a year and a half, and all we got were rejections. And then when I met with him, he said, “Oh, Kwame, I'm sorry I never sent it out. I didn't think your career should be defined by poetry, so I decided not to send it.”

J: Oh brother. Do we still have that agent?

K: Obviously, I fired him.

J: Alright, okay.

K: The thing is, you know, I finally got an offer in 2013 which was enough for me to pay the mortgage, maybe for one or two months, and then, of course, it won the Newbery Medal, and then it got turned into a Disney TV show…

J: Now it’s in Hollywood, right? Okay, so that's the next little trip. Now, how's that been? That experience…we got Disney and LeBron James's company was involved a little bit too? How has that been?

K: Working with Lebron James's company…it afforded me a certain level of leverage that we were able to use. So we didn't have to deal with a lot of BS.

J: And there's a lot of BS to be dealt with out there.

K: I'll tell you, man, oh my goodness. I was told that I couldn't be the showrunner on the show because I had never showrun. I'd never run a show. And my position was, you know, I've written the book. I believe I can do it. Pair me up with another showrunner, and I'll be the co-showrunner. So they bought that, and we co-ran the show, and it was, it was a great experience. It was five years from Disney optioning it to it actually debuting on Disney +.

K: Man, that was one of the most intense…14 hour days, 100 degree weather in New Orleans. Two summers…and it was the most rewarding experience. So to go from having a book rejected 23 times to having it win an Emmy Award for Outstanding Teen Show. That's like the power of resilience and persistence. something you and I both know about, and I think that's a big part of this. Like, do writers have the gut? Do you have the gut to really stick this out?

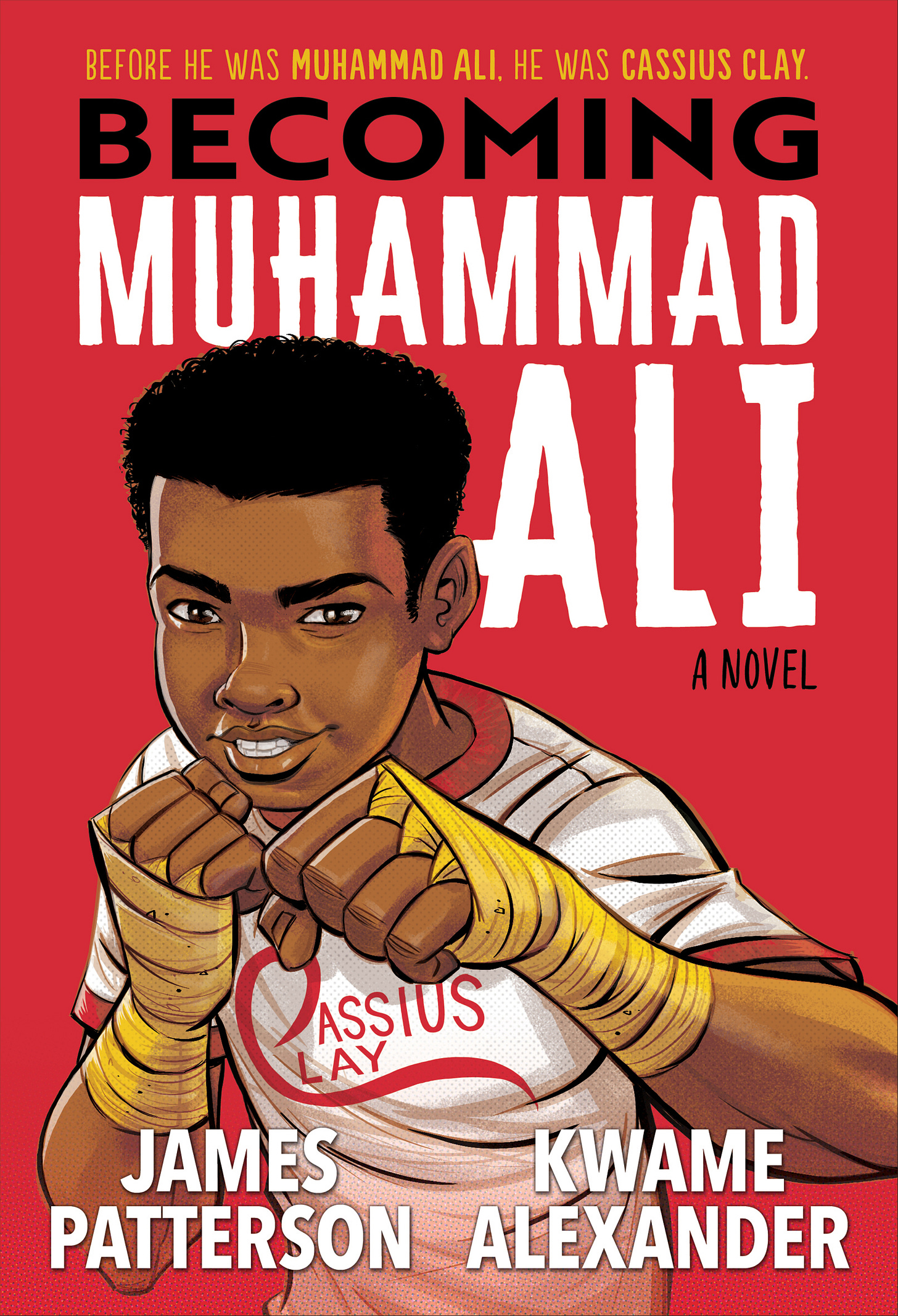

J: Yeah, it’s tough out there. It's tough in the publishing business and getting getting tougher. And in Hollywood, it's a mess. You and I got involved with Becoming Muhammad Ali. We were involved with the Ali estate and Lonnie and all that stuff. And one of the things for me with that book is I found myself for the only time in my life, kind of following you, versus the other way, where I tend to lead. But I was very comfortable with that, partly because of your connection to Ali was so powerful, starting with a book of his, which really was one of the things that turned you on. So you talk a little bit about that.

K: Yeah, when I was 11 or 12, my father had me reading the encyclopedia, dictionaries, his dissertations. I was bored. I wanted to read that stuff, but he made me read them. And I discovered this book in our in our library, our library was in the garage, and there were 50 or so milk crates, green milk crates with books spying out. And I saw this book. It was called The Greatest and I was drawn to that title, and I opened it. And of course, it was the autobiography of Muhammad Ali. And Random House published it in 1977 I believe. And so I read the entire book. I could not put it down. And it did two things for me. Number one, it introduced me to this, you know, confident, almost arrogant, word-weaver, super0athlete, brilliant human being. And so I got to know him.

K: But also what it did was it showed me that books were cool. It reminded me that, okay, books don't have to be stale and incomprehensible and boring. And I read all 478 pages of it. And so when you called me and you introduced this idea of us working on this book together, it was like a no-brainer for me. I knew that I wanted to be able to tell the story of his childhood, which was something that hadn't been done yet.

J: Totally misunderstood, too. I love the way that book…you know, you start every book and you hope that they turn out…some do and some don’t…but I love the way that turned out… the combination of your poetry and some prose. I thought that the two pieces mesh nicely too.

K: They really did, which really is a testament to you, man, because you've done this so much. You figured out a way to get us into the rhythm of it, and it worked. I mean, it was just, it was brilliant…you couldn't have planned that better.

J: Yeah, even The New York Times gave it a good review, and they never review anything with my name on it, so that was cool.

J: You know, you talk about your dad… my father, as I told you, he grew up in the Newburgh poorhouse, and his mother was a charwoman there. She, you know, took care of the kitchens and stuff and whatever, and he was kind of a distant guy. And then your dad was a writer, right? Writer, teacher?

K: Writer, professor, publisher, Baptist minister.

J: I didn't know that piece, okay.

K: Oh yeah, oh yeah. I was in church every Sunday. But he was very distant, like, well, he wasn't very emotive. You know, most men, stereotypically, are not, but he was, he wasn't that guy. It was all about books and literature and the work. I never saw him like, having fun.

J: Now you wrote in Why Fathers Cry at Night, which we'll talk about a little bit at some point. But you wrote “The Heavyweight of Fatherhood” and that had to do with your dad, right?

K: Yeah…he was a wordsmith, but there were times where he would use his words to, like, knock you out, to cut you down.

J: That's how your poetry is, too. That kind of language that which is, it's very, it does hit you in the face or whatever the heck it is, but…you feel it. You feel the words.

K: Yeah, I think I try to do it from a space of of love, of hope, of positivity, but, and that comes from my mom. But my dad was…he was very serious man, and he, he didn't tolerate a whole lot of nonsense. And as a kid, that's all you're into, is a bunch of craziness and nonsense. It was just interesting, having that dichotomy of a very bookish father who was all about the seriousness of words and a very kind and loving mother, who was all about words as a way to uplift and make you feel good and encouragement. So it was a different kind of encouragement coming from both of them. My father said to this day that had he not made me read the dictionary and the encyclopedia, would I still be the writer I am today? He wants royalty payments.

J: Yeah, ha! It's interesting. I did a book on Tiger recently. And on some level, his mother was the tough one…she was the one that said, “You go out there and you kill it…if you're going into the fourth day with nine strokes, I want you to win by sixteen.” She was you know, real talk. I don't mean that in a bad way, but it was an interesting thing. And his father wasn't quite that way.

J: So, you go off to school, Virginia Tech. You study biochemistry. Were you going to become a doctor? What was your notion there?

K: I was going to be a pediatrician. And then I discovered organic chemistry, and I was like, “Okay, this may not be my future.”

J: Let's talk about that a little bit, just in terms of medical schools and stuff like that. Is that right? That seems, to me, to be wrong. You got a smart, empathetic guy here, and we're not going to let him or her in, because they can't do a certain math course, which really doesn't matter that much in terms of being…you know… that seems kind of messed up to me.

K: Well, the messed up part was, I mean, I got a C in organic chemistry, so it wasn't like I failed it. But what I didn't realize, is that I did not need to major in biochemistry in order to go to med school. I could have majored in religion or creative writing, and I didn't know. My advisor hadn't told me that. And so I thought that the path was only biochem or biology or chemistry as a major. And come to find out, it wasn't that. And so is messed up is that I had an advisor who didn't tell me that.

J: You know, so we both have some, I mean, you more than I, but some relationship now to the HBCU schools…and I was just at Howard over the weekend, which was great, because we have some scholarships there, and the kids are just so ridiculously smart. But one of the statistics, which I think it's both cool and a tragedy…60% of the black doctors in this country come from HBCUs, and bless those schools, but also, damn the other schools, because they're messing up. That statistic tells you a lot, it tells you a lot. We really need doctors, and we need good doctors, and we need empathetic doctors and whatever. And they don't have to do organic chemistry, and they don't have to do a lot of crazy mathematics to become good doctors. And somehow, the people that are keeping the gates closed need to open those gates up.

K: I would love to have had a pediatrician who was a poet. I mean, I think they'll probably be more in tune to the human spirit, to the humanity of it all. So, I agree with you.

J: Well also you know that connection between, you know, doctors who who have that bedside manner…that really is very useful, and it's just a whole, I mean, I don't want to bullshit too much in this, but the the mind-body thing about illness and health and whatever, which you know, it seems to be a piece of it. And I'm always, you know, I really like my doctor a lot. I go in there and we laugh, and he says, “you're sick.”

J: But you know, so anyway, so at Virginia Tech, though, that's where you met Nikki Giovanni, though, too, right?

K: She was my professor. She was my professor for three years and and taught me everything I needed to know. But at the time, I was so young and thought I knew everything, so…we didn't get along too well while I was at school, but later on in life, we would become close friends. Now, if I were to say outside of my parents, who had this, you know, the most impact on my writerly pursuits, it would definitely be Nikki Giovanni, because I was able to sort of look at a living poet and use her as a model for what I perhaps, you know, could achieve. You don't hear, you don't hear of a whole lot of poets making a living as a poet, but I got to see her every day for three years make a good living as a poet. So she definitely became a model, not only for how I write, but how I sort of move around the world.

J: And you've done some teaching too, right?

K: I tried to, I tried, yeah, it wasn't for me like that. Have you? Have you taught before?

J: No, I can't. I don't have the patience for it. My mother did for a long time, but I'm just like, I can't do this.

K: It's sacred work, man. I mean, you have the capacity to nurture and develop and build beautiful human beings who you see every day, or if you're not a very good teacher, you could destroy them.

J: Yeah, you can really turn people off. I had one. It was required writing course, undergraduate. He was Catholic poet laureate, whatever the hell that’s supposed to be…sounds like a contradiction in terms. But he said, “You know, you write well enough, but stay away from fiction.” So that was his, that was his advice. He was probably right. But you know, what the heck.

K: Ha!

J: But you have this massive cool imagination and stuff, and even with the kids stuff… like, Acoustic Rooster, which kind of is about getting kids into jazz and stuff, right?

K: Yeah, last weekend, Jim, I got to hang out with Wynton Marsalis. Oh my god. This cat is so cool. And I gave him a copy of Acoustic Rooster, which is about to become a PBS cartoon. And the whole idea around it is to teach, to introduce kids to jazz music. To the instruments, to this idea that Wynton talks about that jazz is a great metaphor for democracy, Jim… in that you got your sax, your horns, your drums, your keys, your vocalist, everybody has to be able to play together. And at any given time, someone's going to be out front soloing, and the other folks are going to step back and allow them to do their thing.

J: I think that's totally right. Totally right. It’s not what you expect. Which it shouldn't be..I mean, yes, you can work music together that's a little bit more familiar for people, right? But no, that's not how democracy works…I tell you what, you know, I'm not going to get political. But listening to the Democratic Convention, and there was some emotional stuff, but I stayed dry-eyed…but I did cry twice during Kamala’s thing, and it all had to do with her talking about unity. And I hope that we can inch toward that a little bit, because that's how we get saved. Just move it in that direction a bit.

J: Now you have another thing going in Hollywood too, right? That they're developing?

K: I'm sort of in the process of creating a one-man-show based on the memoir, Why Fathers Cry at Night.

J: Well…we're both dads, obviously. And, you know, we go through what we go through. But let's talk a little bit about that in terms of why you wanted to write (Why Fathers Cry at Night), and you wrote it to your daughters, right?

K: I think I thought I was writing it to my daughter. It turns out…I was writing it to my mother, who had passed away in 2017 so I thought I was writing as a father, when in reality, I'm writing as a son trying to understand and reconcile and deal with all the ways I've sort of succeeded and failed at love. It is one of the one of the hardest books I've ever written, and it really allowed me to examine how I move as a father, as a son, as a friend, as a lover, as as you know, just trying to figure all that out. So it was really probably the toughest thing I've ever written. Would you say the same thing about your memoir?

J: No, no, no, no, no. It was just joy from the beginning to the end. I wrote it during COVID, I didn't have anything better to do. I just started writing down stories.

K: Wow.

J: And it wasn't one little thing. I write about a page about my hometown, Newburgh, and all that historical horseshit. And I said…“if you're looking for that kind of stuff, it's not here.” So it's just story after story after story. Like I mentioned, with my dad and and growing up the way he grew up, and he was going off to war, and it's in the book, but he got this call from this guy, and the guy said, “Just stick with me for a little bit. My name is George Hazelton. I live in Port Jervis… I'm about to go off to the war. And last night, my parents, after dinner, they took me down to the living room, and they said, “George, we love you so much, and you're going off to war. So we have to tell you that when you were like, one and a half, we adopted you, and we never told you you were adopted.” Then over the phone, this guy said to my father, “I'm your brother.”

K: Wow.

J: And that's how my father found out that he had a brother. So it's all stories like that…some of them are goofy, you know, like playing baseball as a kid…but cool stories. You know it gets into different things about my parents are both, you know, alcoholics and whatever. So gets into stuff, but I didn't feel like I was on the on this psychiatrist thing. Ha ha.

K: Hey look, when I was on book tour for it (Why Fathers Cry at Night), every night felt like a therapy session. I'm dealing with things like, you know, being separated. I'm dealing with, like my mother's passing. I'm dealing with with my oldest daughter who is estranged, and so all these things I'm dealing with in this book. And so it was therapeutic and cathartic. You know, my father read it, and he said, “I read your little memoir, Kwame.” He was sort of in his feelings, you know. But ultimately, Jim, I think it did what it was supposed to do. It helped me, sort of, you know, fix some things that were necessary to be fixed.

J: With shrinks, I did one year, and it was good. I like the guy, we actually would go out to lunch after I said I've had enough, and we go out to lunch about once a month after that. And the one thing I always say to people in therapy. Don't let them bullshit you. You start right away talking about your mom and your dad. Just get into it right there. Because no matter what, that's going to be a big piece of it, pretty much for almost everybody, get right into it. Don't be shy about it. Save yourself some money…but getting back to to that book, “A Poet Walks into a Bookstore”, that's interesting…tell us a little bit about that, because I really like that poem.

K: I was writing a lot of love poems. You know, most of the poems I wrote at the beginning of my career were love poems. That's that's been my space that I enjoy. And I feel like, you know, I remember walking into this bookstore in Washington, DC and and asking the bookstore manager if they would carry my book. And this is a book that I published myself. So this is back in the late 1990s or early 2000s and I showed her a copy of the book, and it’s high quality, beautiful imagery, designed nicely. I paid a lot of money for it, and she said, “Oh, this is love poems…we don't sell love poems here.” Implying, we only really sell serious books. And I just looked at it, I was like, “What's more serious than than love?” It's all about relationships and the people you love and people who love you, people you care about in this world. And she just wouldn't she, she's like, “We're not selling love poems.” I just found that to be interesting and ironic.

J: Bookstores need to be doing, “Come in, come in, come in!” And not, “Stay away, stay away, stay away.” And libraries…“Come in, come in, come in..you're welcome.” You know this phrase “guilty pleasures” about books. I don't buy that, man. To me, if you go into a bookstore, period, you put a star on your cheek. If you go into a library, put a star on your thing. If you read a book, put a star on your forehead. This is a good thing. It's okay. Whatever it is, whatever it is, it's okay. You just keep reading. And that's a good thing and and that'll help more writers get to write.

K: Years later she would, they would, end up having all of my books in the store. Of course, they eventually got around to it. But yeah, it always sort of bothered me.

J: Yeah once again, that, that thing of like, invite them in. You want to read John Grisham? Cool. You know, that's great. You want Patterson? Whatever the heck it is, that's okay. That's fine. We don't look down on that stuff.

K: Right. Right. Yeah.

J: The kid stuff that you know, as I'm sure you're, you know all too well. Now, it's getting harder and harder and harder to get kids’ books into stores.

K: Oh my gosh, yeah.

J: It's a mess, yeah, and that's happened the last three or four years. I mean, it's really gotten messy. And that's awful. That's awful.

K: Not even just with books. When you look at what's happening with children's television programming like this, so many companies are laying off and cutting staff and cutting programming. It's, yeah, there's something happening in this world that isn't it doesn't seem like it's going in the right direction when it comes to to entertainment in particular.

J: Yeah, yeah. The kids just want to watch the big, the multi-million dollar Deadpool. “I can watch Deadpool.” “Well, you're seven years old…hold on here.” Nothing against Deadpool, but that seems to be what they do. And then, you know, and I don't know it's a crazy thing. And book banning and all that stuff.

J: Have you been banned yet?

K: I have.

J: Me too. Yahoo! Ha.

K: I was banned in a place in Texas, and my friend said, “Well, how do you feel about it?” And I don't feel a certain kind of way but I'm gonna do something about it. So I flew to the city in Texas, and I showed up at a school where I knew a teacher had taught my books at one point, and and I read to the kids from the book that was banned. I can actually understand how some of these parents feel, because I don’t necessarily want my 12-year-old watching Bridgerton. Like, I get it. I'm just not going to tell you your kid can't watch Bridgerton.

J: That's exactly where I'm at on it. You take care of your house. I'll take care of my house. No, I don't want a stranger telling my family what they should and shouldn't read just you take care of your own stuff, and that's okay. You should. You should take care of your own - you have your own deal, whatever it is, but stay out of mine. You know, I didn't have to go to Texas because it was close in Florida, but I went up into a couple of the meetings there, sat in and, you know, you just go, come on, this is crazy. I mean, they were they banning Maximum Ride in a couple of counties and you go, what? Maximum Ride never hurt you. And it was one woman in one county, she just went in and she said, this is inappropriate, and she hadn't read it. And you know, what are you talking about? If you read it and you tell me, why? Okay…because, what? Because the kids can fly? I don't know what, what's wrong there, but right, tell me what is it? What's what's going on here? Yeah, it's crazy.

K: Yeah, it's absurd. It's absurd. We're doing a banned books town hall meeting to have some conversation and discussions around it. But I just think people are generally just afraid and and I get it as a parent, yeah, our goal to protect our kids. I get it, but don't try to protect my kid for me, like I know what's best for my kid.

J: Yeah, and don't be beating up booksellers and the librarians, they have a tough enough job, and the teachers. I mean, there's just so many “listen to the left, listen to the right, listen to the parents, listen to the kids.” I mean, that's just that job, and that's an important job. And a lot of people go, I don't know if I want to do that. That's become a really, really tough job. Crazy,

K: Instead of banning books, we should be talking about banning guns. Is my feeling.

J: No, I'm there. I'm there. Especially, I could, honestly, ban them all, but in particular, these machine guns. I'm sorry. I mean, what? How? Why? You’re gonna shoot your dinner with a machine gun? I don't think so. That's a bad idea.

J: Well, look, this is great. Anything that we missed? What’s next for you? Oh, you got, you got your trilogy? Black Star?

K: Black Star comes out September 24th and that's book two. I'm writing book three. And so book one takes place in 1860. Book two takes place in 1920. I'm thinking, Jim, about book three, like really taking a serious time leap and going in the future. So we'll see if I can pull it off.

J: All right, you can pull it off. We know how to figure stuff out. We do know how to pull stuff off.

K: Yeah, it's true.

J: Alright. Well, this has been a treat for me.

K: Thank you, man.

J: Glad to see you're back in DC. Missed you.

K: You too, man, I look forward to seeing you soon.

Share this post