“We're here! This is free Wednesday, and that means you don't have to pay anything (but you don't get Mondays and Fridays - which are really great).

And we're just trying to give away a bunch of stuff on Wednesdays. Some of it's going to be goofy, like pencils with erasers that I bite when I'm writing.

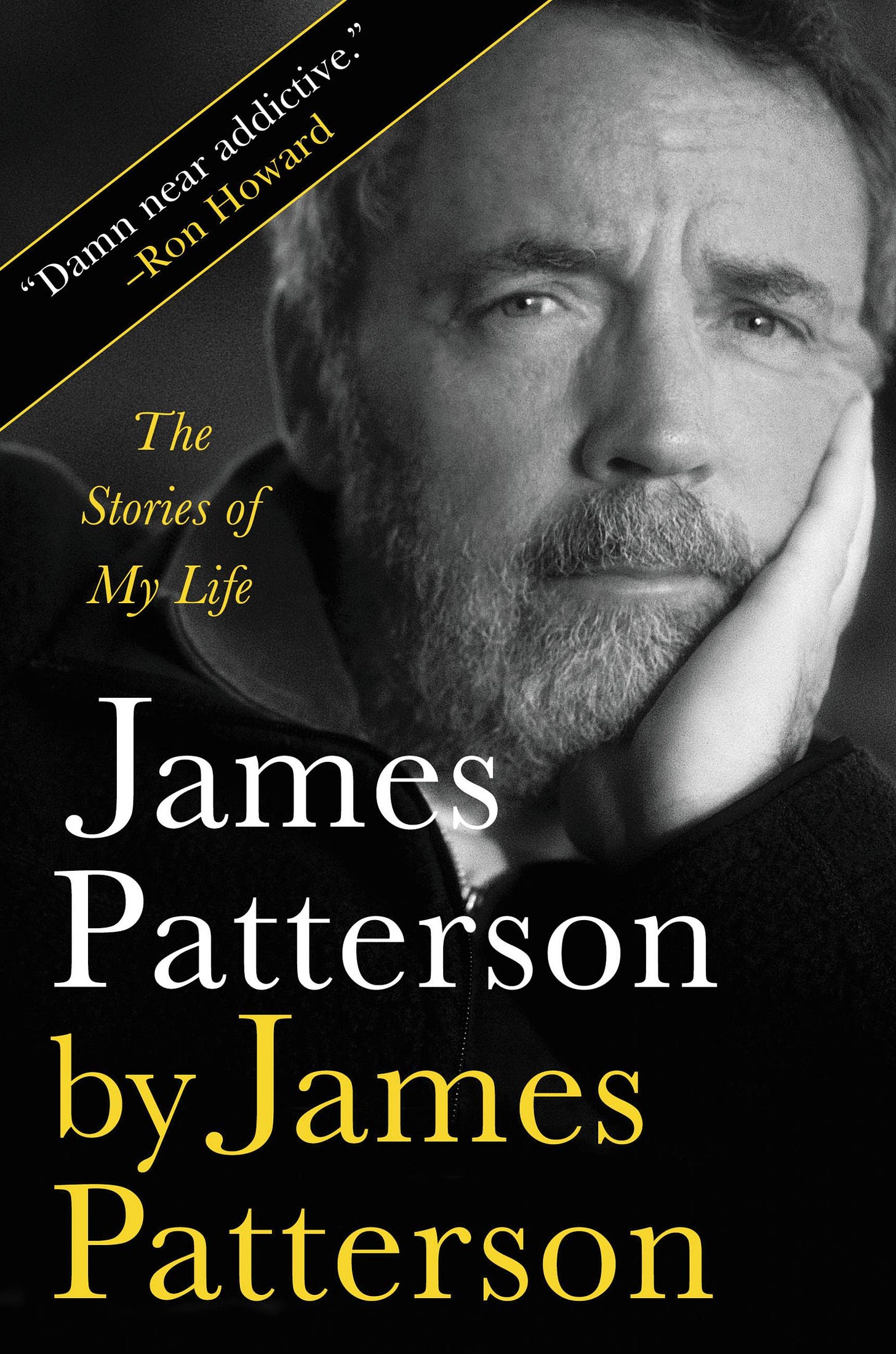

I want to talk about my autobiography, James Patterson by James Patterson, which is the whole title. Over the course of, I don't know, a couple of months or whatever the heck, we'll give away all the chapters to that. We'll give away chapters to other books that haven't been published yet. We'll try to make it interesting…

Doing my autobiography at this age - it made me a better writer. It really got me to concentrate more on sentences. Some of you out there, some of you writers, think you're better than I am, and maybe you are, maybe you aren't, but you'll read it as the chapters come along, James Patterson by James Patterson, and you’ll come to your own judgment about your own writing and my writing, and that'll be kind of fun…”

See below for FREE chapters from my autobiography, James Patterson by James Patterson.

James Patterson by James Patterson

“Texas-Style”

I try my best not to get political, especially when I’m interviewed on television. I’m not comfortable broadcasting my political or socioeconomic opinions, and I usually get itchy and twitchy watching other writers or actors getting up on soapboxes they don’t always deserve to be standing on. I don’t believe everything in life comes down to politics, but sometimes I feel like I’m one of the very few people thinking that way. I guess I consider myself an Independent. I definitely want to hear what everybody has to say, both sides of the argument.

Anyway, in 2004, the Bushes invited Sue and me to Fort Worth for the fifteenth anniversary of Barbara’s Foundation for Family Literacy. The program was driven by Mrs. Bush’s belief that “the home is a child’s first school, the parent is a child’s first teacher, and reading is a child’s first subject.”

Let your children see you read.

Sue and I spent the day with George H. W. and Barbara. David Halberstam was there and we talked about The Best and the Brightest, his narrative of America’s involvement in Vietnam that the Boston Globe had likened to “watching an Alfred Hitchcock thriller,” and about his time in Moscow. The novelist Daniel Silva was also at the Bushes’. I’m a fan of Silva’s wonderfully complex Israeli hero, or maybe antihero, Gabriel Allon. Silva can really write. The bastard.

While we were at the Bush apartment, Barbara pretty much ran the show. But every once in a while President Bush would sneak her a look that communicated Okay, enough. Let’s not forget I was president. And Barbara would give him a look that seemed to say Heard that one before.

I found the Bushes to be down-to-earth and they both had a terrific sense of humor. When some people get a little too over-the-top negative about Bill and Hillary Clinton, I’ll say to them, “You respect the Bushes, right?” If they’re being honest, most will admit, “Yeah, yeah, the Bushes are good people.” Then I come back with “Well, the Bushes love the Clintons. So that’s got to tell you something about the Clintons.” The two families were close, especially President Clinton and 41.

It seems to me there’s a nasty little disease going around and it’s especially prevalent on TV and radio news shows. It goes something like this: “My view of the world is right — and your view is stupid!” I really don’t like that. Honestly, it makes me a little sick to my stomach.

Do I believe Al Franken should have had his Senate career ruined? My personal opinion — no. Do I know what went on between Woody Allen and the Farrows? Nope. And neither do you. And neither did the Hachette Book Group employees, none of whom had read Allen’s autobiography Apropos of Nothing, when they demanded the publisher not publish it. Maybe I’m hopelessly old-fashioned, but I’m almost always on the side of free speech.

“Golfing with Presidents ”

I’ve played golf with three presidents — 41, 42, and 45.

George Bush Senior, 41, ran around the course like the Energizer Bunny. He seemed to have a really good time doing it. George H. W. was a movie-superhero blur out there.

President Clinton and I have played four or five rounds and it’s always been a blast. When we’re together, it’s just two hackers messing around. We’ll hit extra balls, occasionally land some really good shots and some bad ones. It’s never serious when we play. No ten-dollar bets. An occasional mulligan.

The two of us were photographed repeatedly on the course during an interview for Sports Illustrated. I tried to set the tone of the story for the writer, Jack McCallum. President Clinton and I were just going to go out there and have some fun. No scorecards.

McCallum wanted to cause some trouble, of course. That’s what he’s supposed to do. It’s his job. So he asked which one of us was the better golfer. I told him, “Well, President Clinton is faster giving a four-foot putt. I’m faster dropping a second ball after a bad shot.”

On we went to the first hole, a par five.

I hate to admit this in print, but I muffed my second shot into the rough. Just to be sure I had made my point with McCallum, I yelled over to him, “Hey, make yourself useful, Jack. Pick up that stray ball for me.” Fortunately, he thought that was pretty funny. Then I showed him how quickly I could drop a second ball.

I’ve also played with President Trump. So has President Clinton. Donald Trump is a serious golfer, easily the best golfer of the presidents I’ve played with. He’s somewhere between a four and six handicapper. For real. And I have no reason to make that up.

Before Donald Trump was president and before I had collaborated with President Clinton on a novel, I took two friends of mine to play at Trump National in Westchester. My friends and I had grown up together in Newburgh and I figured it would be a story for them just to be on one of Trump’s courses.

So, we’re playing the third or fourth hole, and one of my friends looks over to the sixth hole. His eyes go wide. “Is that Donald Trump? Is that President Clinton?”

Yes, it was. Trump and Clinton were playing golf together, which is its own interesting piece of history. It’s the way things used to be in politics, though. Better, saner times.

My friends and I finished our round and got to the clubhouse just as Donald Trump and President Clinton were getting up from lunch.

We started walking across the dining room and President Clinton was staring at me. Normally, I wouldn’t have bothered him, but I said, “Hi, I’m Jim Patterson.”

Clinton said, “Oh, I know who you are. I recognized you right away.”

I said, “Well, I recognized you too.”

At that point, my buddies, Bob Hatfield and Mike Smith, who were both card-carrying Republicans, asked if they could take a picture with President Clinton. I decided it would be another great story for them to bring home to Newburgh, but I would sit this one out.

I hunkered down at a dining table and watched them do some mischief out on the lawn. Melania took a photograph of my friends with President Clinton.

Then I watched them shaking Donald Trump’s hand. I knew he didn’t like to shake hands. When they got back to the table, I asked, “What was going on with Donald Trump out there?”

My friend Bobby Hatfield said, “We told him we played basketball against him in high school.” This was true enough. Donald Trump went to New York Military Academy, which is located not far from Newburgh. Our schools had played against one another. Trump said to my friends, “I hope we won.”

Hatfield said, “Nah, we kicked your ass.” Both Donald Trump and President Clinton got a laugh out of that one. What an image. Donald Trump and Bill Clinton enjoying a good laugh together.

One more story.

In the fall of 2019, Little, Brown was contacted and told I was being considered for either the National Humanities Medal or a National Medal of Arts. In the past, the National Medal of Arts had been awarded to my old lunch pal John Updike, Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, August Wilson, Philip Roth. My publisher was informed that I might get a call from the White House.

The call came one Friday while I was working in my home office. A very official-sounding male on the line said, “Please hold for the president.”

I couldn’t resist and I said, “Which president?”

The award ceremony at the White House was very gracious and memorable for Sue and me and the Little, Brown people.

“You Called the President What? ”

As I said earlier, President Clinton and I have played golf together a few times. Of course, there had to be a first time. When you’re with a former president, you have to feel your way. What we’ve evolved to is that when we are in public together, everything is appropriately respectful — Mr. President this, Mr. President that — but in private, we’re just two guys.

Up to a point. Hell, the man had been the most powerful person on the planet. You don’t get over that. I guess. How would I know? I’m not even the most powerful person in my house.

The first time we went golfing, Tina Flournoy, President Clinton’s brilliant chief of staff (she’s now Vice President Kamala Harris’s chief of staff ), told me, “The president will only play nine holes.” I’m like, That’s fine. It’s cool. I’m okay if he only wants to play one hole. Or we could have a putting contest on the practice green.

So we played. He drove the golf cart — and think about it, Bill Clinton has driven a car like twice in the last twenty years. He’s dangerous on the cart paths. Pedal to the metal even flying down steep hills, on the sides of hills, skirting streams and ponds, crossing a highway where real cars go real fast.

Anyway, on the fourth or fifth hole, he had a putt for birdie. It was a short putt, maybe eight feet. He left it three feet short.

Now, if you play golf, you know you just don’t leave a birdie putt short. And definitely not three feet short. And that’s why a word came out of my mouth that I never expected to say to a president. “You [the word I never expected to say to a president]!” President Clinton said, “Did you just call me a [the word I never expected to say to a president]?” I nodded. Then he said, “Well, you’re right, I am a [the word I never expected a president to say].”

And that mildly blue exchange sort of set the tone for us. When nobody’s around, we’re just two human beings.

That first nine we played turned into eighteen holes. He was enjoying himself. So was I.

Around the twelfth hole, Hillary called. She was off on a book tour. The president told her, “Oh, I’m out here with Jim. We’re having a great time. We’re like two high-school boys playing hooky.”

He and Hillary talked for about five minutes and at the end of the call, he said, “I love you.” I don’t think a lot of people expect that Bill and Hillary are like that. Those people couldn’t be more wrong.

The first time my wife, Sue, and I went out to dinner with them, we noticed that two or three times during the meal they were holding hands under the table. What can I say — I love that.

It reminds me of the way I am with Sue. Every night — and I mean every night — she and I go to sleep holding hands.

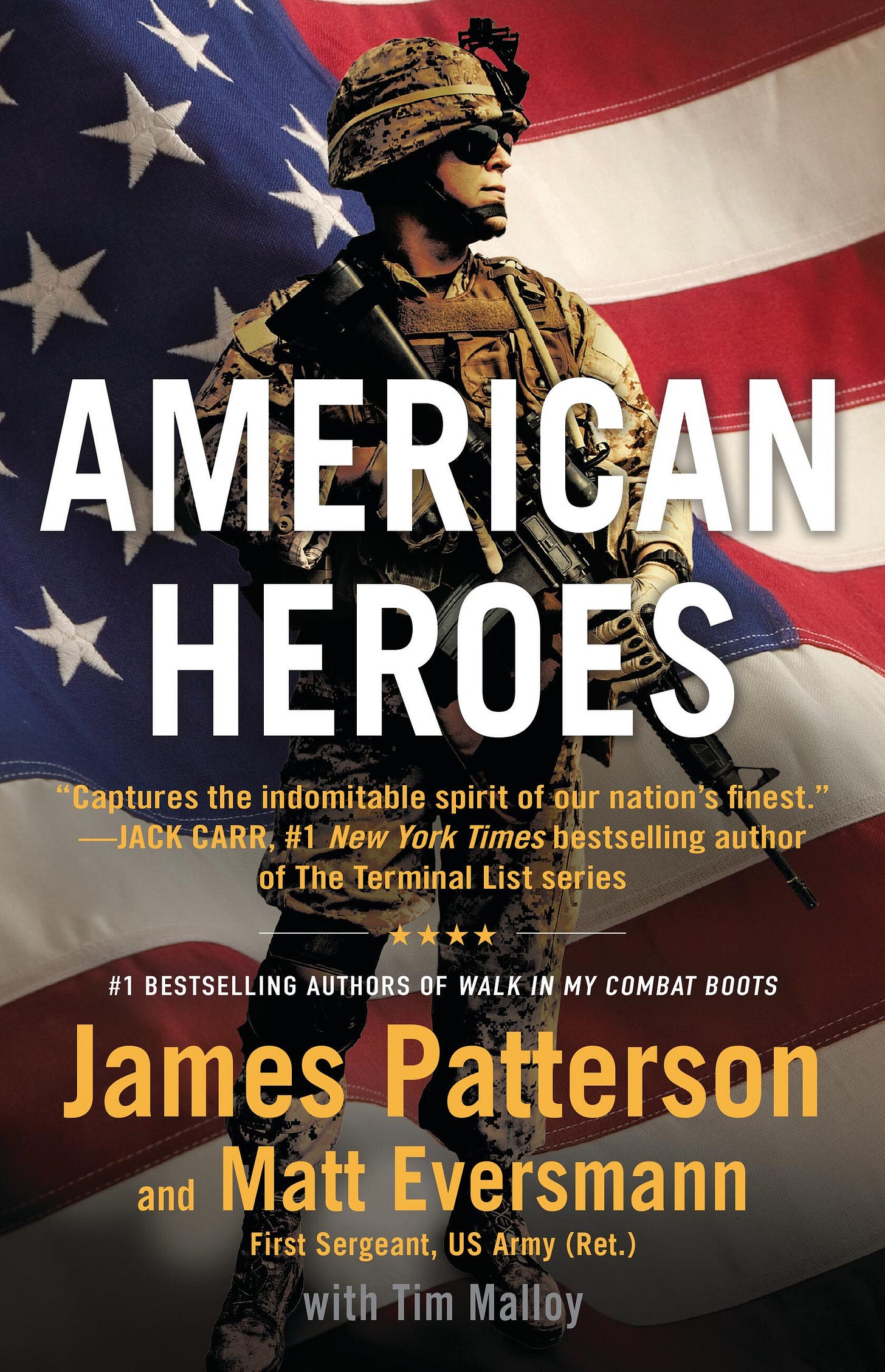

AN AMERICAN HERO: Brian Kitching

My coauthor, Matt Eversmann, talks to his fellow comrade, Brian Kitching.

See below for Brian Kitching’s incredible excerpt from our #1 bestselling book, American Heroes.

It’s the middle of the night. My brother Julian and I are sitting in my beat‑up car, talking about our futures. I’m grappling with how to find more purpose through leadership and service.

“If that’s what you’re really interested in,” my brother tells me, “you might want to consider joining the Army.”

It’s what he really wants to do, but he’s working through some health challenges. (Julian will go on to have a distinguished career as a Green Beret.)

I’ve recently started college in Huntsville, Alabama. That night, I decide to drop out and enlist.

“You’re throwing your life away,” friends and family say. “You’re going down the wrong path.”

I do it anyway.

My first duty station is Fort Campbell, located on the Kentucky‑Tennessee border and home to the Army’s storied 101st Airborne Division. My report date is September 11, 2000. I don’t know anything about how the Army works. I’m the first in my family to serve. I didn’t have anyone in my life who could coach me on so many of the dynamics unique to the

Army and military writ large.

But I instantly connect with Army life, and I’m fascinated by the stories of people from all over the US and world who have volunteered to serve our country. I’m also fortunate to have mentors who encourage and challenge me to always care for people and strive for excellence.

It’s not long before we all face a challenge that changes everything.

One morning, I’m putting my camouflage uniform on as I’m walking down the hallway in the barracks. I look over at a TV and see two big office towers on fire.

“Is this a movie?” I ask the other soldiers in the room. It’s September 11, 2001.

Leaders begin yelling, “Go to the arms room and draw your M4!” Everyone is grabbing their rucksacks and weapons and scrambling to secure different areas of Fort Campbell. In the following days and weeks, security at Fort Campbell tightens dramatically, and our training schedule intensifies.

Over the course of the next several months, we receive information slowly — and train relentlessly. Our infantry pla‑ toon sergeant has us stand in formation while he reads aloud accounts from combat in Afghanistan. For someone who has just joined the Army, I struggle to imagine what combat looks like halfway around the world.

In March 2002, I deploy to Afghanistan as our brigade finishes wrapping up Operation Anaconda. I’m a corporal, a for‑ ward observer for 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment (Rakkasans). Essentially, my job is to conduct intelligence activities and call for indirect fire from mortars, close combat aviation, or in some cases, fighter jets. It’s unclear how long we’ll be in‑country.

Almost no one in our formation has any substantive combat experience. Many of us assume that we’ll be facing direct combat the moment we hit the ground.

That’s not what happens. When we land at Kandahar Airfield, the forward operating base (FOB) is still in the process of being built out. There are minimal combat patrols on that first deployment.

Our days are filled with various work details, rehearsing for potential missions, and pulling guard duty for detainees. We train constantly, and sit around our tents talking about home, or whether we’ll see action.

One day, General John “Jack” Keane addresses our formation. “Make no mistake, we’re going to be over here for a long time.”

“No way, we’re going to be out of here in no time,” mumbles one of the young officers standing near me.

A few months into the deployment, I’m notified that I’d been accepted into the Army’s Green to Gold program. It selects enlisted members to complete college and become commissioned officers.

Over the next decade, I finish college as an Infantry officer, and after completing Ranger School, I deploy to Afghanistan three more times as a platoon leader — once with the 82nd Airborne Division, and twice with the 75th Ranger Regiment, the Army’s premier raid force.

I take command of a mechanized infantry company (essentially, an infantry company that delivers soldiers via the Bradley fight‑ ing vehicle) in November 2011. Only a few weeks later, I’m notified that we’ll be deploying to Afghanistan. We’ll be relying principally on our feet to do the job.

We deploy in March 2012. This will be the first Afghanistan deployment for most of the soldiers and leaders in the company. Most of these soldiers are brand‑new to the Army, kids who have only qualified on their weapons in basic training. Many of the leaders have several combat experiences from Iraq, but this combat will be different.

Most of them have relied heavily on vehicles to conduct operations — and there isn’t a strong culture of dismounted operations. Up to this point, I’ve always prioritized combat‑ focused training in the organizations I led, but when I learn of the specific area where we will be in Afghanistan, it gives me pause. I know I’ll have to intensify our efforts.

The district of Panjwai in Kandahar Province is notorious. It’s one of the birthplaces of the Taliban and known for fierce, well‑equipped fighters and elaborate improvised explosive device (IED) tactics. It’s also one of the most violent areas in the entire country.

Generally, I think it’s more effective to spend time cultivating a greater sense of buy-in within a team, but we don’t have the luxury. In the ninety days leading up to the deployment, we push our soldiers hard, emphasizing extended foot movements, functional fitness, nutrition, and patrolling tactics. We study our enemy’s tactics and regularly review real‑time reporting from the unit we’ll be replacing.

“This is the way we must train in order to meet the demands of combat,” I tell them.

Our company operates out of Combat Outpost (COP) Sperwan Ghar, a towering, man‑made piece of terrain in Panjwai District, Kandahar Province, west of Kandahar City. I’m one of three people in the 135‑man unit with previous combat experience in Afghanistan. A company of Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers is colocated with us.

Our mission is to prevent the Taliban’s ability to destabilize Kandahar City with large‑scale attacks. That means finding and destroying weapons, explosives, and fighters attempting to organize operations against our partnered Afghan forces.

We quickly begin conducting operations in our area. Within weeks, we destabilize the Taliban’s operations, knocking out key IED and drug facilities. We patrol day and night. We’re disciplined with after‑action reviews, and we’re continuously refining our tactics based on the operational environment. The noncommissioned officers and young soldiers of the company perform with astonishing bravery every day.

But our operational successes come at significant cost. By September, we’ve lost five men, with more than a dozen wounded.

Our company is scheduled to redeploy in December, and the fighting hasn’t let up.

In late September, I’m given the objective to conduct a company helicopter assault in a village named Nejat, to clear and destroy the village’s IED facilities. Nejat is by far the most dangerous village in our area of operations — notorious for running drugs and weapons. Its tight clusters of mud structures and mazelike paths make it a nightmare for IED attacks. Of the two hundred–plus battles in my area of operations over the course of the nine‑month deployment, almost forty have occurred in Nejat alone.

We infill the company on CH‑47 helicopters on October 3, 2012, and I spend the evening with 3rd Platoon, clearing the east part of the village. Second platoon is running logistics for us and resupplying as we clear the area on foot. By the time night falls, we’ve engaged in several firefights. I grab a couple hours’ sleep on the dirt next to my radio telephone operator (RTO).

The next morning, on October 4, we link up with 1st Pla‑ toon to finish clearing the last group of buildings in the east while 3rd Platoon moves to clear the southern portion of the village.

Because of the IEDs in the area, we go to extreme lengths to limit the enemy’s ability to predict our approach. I insist we vary the design of our movement formations and routes to get into the villages. We travel in single rows (files), often dispersed, sometimes climbing mud walls, or using axes and picks to tear them down. But it’s incredibly hard, slow work. Brutal. Covering eight hundred or so meters can take hours.

On October 4, we move in a file, even though there’re thirty of us, plus some ANA soldiers. What’s also taking time is that at the front of the formation, I have someone searching for IEDs with a dual‑sensor handheld detector. It uses ground‑penetrating radar and metal detection technology that can locate IEDs even if they’re buried a bit deeper into the ground. The clearing device isn’t great, but most of the time, it’s better than nothing. It’s the only one 1st Platoon has, which creates an additional risk for us.

The day is heating up when I start receiving reports through my RTO about intercepted radio traffic. The Taliban is watching us and is planning an attack.

Many times, it’s a bluff meant to scare us off. But in this area, anytime I receive those reports, there’s always been a fight. We move into an area of the village with a maze of sharp turns and alleyways, and disperse to clear a series of reported IED facilities. It’s the afternoon, and I can tell the men are exhausted, hot, and nearly out of water.

Nejat is relatively quiet. When we get to an intersection, my RTO reports that the Taliban is close enough to hear us.

“Freeze,” I tell the fire team. “Do not move.”

I have thirty people with me; one wrong move and we could potentially trigger an explosion.

All our “elements” — individual squads, platoons, and other units — are spread out. They won’t be able to support, and the high chance of friendly fire in this area would be too risky. Not to mention all the IEDs.

I pull a set of graphics from my pocket so I can orient myself.

As I look to the north, an AK fires at us from about fifty to seventy meters away.

We return fire and look for cover.

When we break back to the rest of the formation, I direct one of the team leaders to use an M320 Grenade Launcher Module (GLM) to fire multiple grenades onto the enemy’s position.

Reports say there are five to seven fighters. After ten minutes of fighting, the enemy breaks contact.

Staff Sergeant D, a phenomenal NCO and one of the fittest guys in the company, is operating the mine‑clearing device. The day is incredibly hot. When we approach a gate leading to the final sets of compounds, a lot of people are low on water.

The staff sergeant stops by the gate and says, “I’m getting a high reading.”

“Let’s use one of the line charges,” I say. We worked with a nearby Special Forces detachment and made line charges from detonation cord, or “det cord” — thin and flexible plastic tubes filled with explosives — attached to C4. It’s much more efficient than carrying around the heavier device that launches line charges. We throw a line charge onto the path and, sure enough, two IEDs detonate.

We move around the gate, into a huge marijuana field that’s around two hundred by two hundred meters. The plants are massive, probably twelve feet tall, and provide us some concealment, but no cover. And it’s hard to stay quiet when you have thirty guys moving single file, trying to avoid IEDs.

We’re probably midway through the field when we start getting hammered by heavy machine gun fire from a PKM, a Soviet‑manufactured machine gun with a muzzle velocity of seven hundred meters per second.

Everyone drops to the ground as rounds cut down the plants and leaves around us. I’m in the middle of the formation, screaming at everyone to return fire. No one does. They’re physically and emotionally exhausted and possibly suffering heat exhaustion, disoriented from dehydration. Most of them are kids. While they’re trying — wanting — to do the right thing, their capacity is somewhat limited.

Two people have been wounded — one of my squad leaders and an ANA soldier. At the moment, there’s very little I can do to affect the tactical situation while stuck in the middle of a marijuana field. I need to get to the front.

I emerge from the field and see a few soldiers being treated for injuries. My RTO and I find cover behind a small dirt wall and receive reports on the wounded. The rest of the platoon begins returning fire.

I direct my RTO to initiate the call for the medevac aircraft. We start to return fire. We’re pinned down in an open area, and we need help. I call for attack helicopter support.

A pair of Apaches arrive and identify ten to twelve fighters moving amid a maze of paths and firing at our position with PKMs, AK‑47s, and RPGs. Our helicopters engage enemy positions while we wait for the medevac to arrive.

The helicopters begin firing and launching rockets into the village. I mark the landing site for the medevac with smoke, but the helicopter flies directly over the landing zone and lands in an adjacent field — with an eight‑foot wall between us.

Why didn’t they land in the LZ? Did they see something that scared them? Made them nervous?

There’s no way we can move our wounded over that wall in the middle of a firefight. “Stay here,” I tell my RTO, and break into a run.

It’s so hot. I’m dripping sweat.

I run about fifty yards and find a break in the wall large enough to go through. I sprint to the helicopter and direct the pilot to go back to the area we marked. It’s not far, but the helicopter’s got to go over the wall.

As the pilot moves over the wall, the helicopter starts taking gunfire from various positions. As we return fire, I’m hoping and praying the enemy doesn’t launch an RPG at the helicopter. We’re only able to get one of the casualties on the medevac helicopter before it’s forced to take off. The other wounded will have to continue the mission. There’s no way that medevac helicopter is coming back.

The enemy gunfire was coming from a cluster of compounds about one hundred meters away. I see huge flames leaping into the air from a large pile of trash and straw that got hit by a rocket from one of our attack helicopters.

I do a water check. These kids barely have any. I can tell they’re all smoked.

We need to move forward and continue our mission of clearing the rest of the village. We still have adequate ammunition and two Apaches in the area.

We move up to a wall. This one is ten feet high. I climb it and drop into the first compound. After I establish security, I tell Staff Sergeant D to follow.

“I want you to establish security east of our position,” I say, taking the mine‑clearing device from him. “I’m going to clear the courtyard of this structure so we can get the rest of the platoon safely out of this open area.” I’m thinking, I don’t really know how to use this thing, but I’ve got to demonstrate some courage and confidence for these soldiers if we’re going to get this done and get out safely.

When I’m relatively certain the area is safe, I give the go‑ahead and the rest of the platoon starts flowing into the courtyard. We take some pop shots from a fighter with an AK‑47, but we’re somewhat protected by the surrounding walls.

Staff Sergeant D, now back to working the mine‑clearing device, says he’s getting readings for potential IEDs.

My RTO receives a report. “The Taliban wants to bring in ‘more friends and the big gun.’ ” He says this in front of most of the soldiers. I wish he hadn’t.

I’m pretty sure it’s just a tactic, but the fighters in Nejat are well equipped. These kids are terrified. I can see it in their eyes. I’ve spent more time in Nejat than anyone else on the ground. I’ve moved multiple platoons through this village and know the area inside and out.

There’s an open area that leads to a wall a hundred yards away, directly to our front. Behind that wall is the final group‑ ing of structures we need to clear.

It’s no one’s job but yours to get your men to safety, I tell myself.

No one else will be able to do this.

“I’m going to make that run,” I say to one of my teams. “Cover me, and I’ll secure the other side.”

It’s the longest run of my life.

I make it to the other side, start pulling security, and we’re able to bring the rest of the platoon up.

“We’re getting too many readings,” the platoon leader says, meaning he assesses there are a lot more IEDs somewhere around us. “I don’t know what we should do.”

My soldiers have been fighting most of the day. Some are close to becoming heat casualties. No one wants to move. Out of the hundreds of patrols I’ve been on, I’ve never seen this level of fatigue — but we can’t stay put.

I clear the last few structures on my own, attempting to complete our mission. The Afghan Army soldiers refuse to assist. I report to my battalion commander that we’re complete with the objective. I tell my soldiers we’re going to move to the exfil point outside the village.

Given the IED threat, this will be an extremely risky movement.

The only way we’re going to make it out of here is if I lead us out. These men have fought so hard and sacrificed so much this deployment. I go to the front of the formation and tell my men that I’m going to lead the way. Staff Sergeant D will follow from a safe distance. We have only the one mine‑clearing device, and my soldiers will need it if I get killed leading them to the exfil point — and there’s a strong chance I will.

I take a moment to mentally say goodbye to my wife and son. I love them so much.

I know this area of the village well. I walk north as the point man, choosing my path carefully where the dirt is packed almost like concrete, and keeping my weapon at the ready should enemy fighters emerge from one of the alleyways. My heart pounds with every step.

As I skirt around a crumbling wall, multiple IEDs detonate, one directly in front of me and another one directly behind me.

I’m blown into a wall. When I regain awareness, all I can see is dirt and dust swirling, pebbles falling around me. Then I hear people yelling. I get on the radio, and as I start asking for reports, I look up and see the mine‑clearing device, broken in half, suspended in a tree.

I don’t see Staff Sergeant D anywhere.

We find him lying face down in a nearby creek. One leg is gone, the other mangled. Blood is running downstream. My RTO and a couple of other guys jump in the creek to retrieve the wounded staff sergeant.

I send the casualty report over the radio, and the platoon medic, in the rear of the formation, moves up to respond.

As he does, he triggers another IED. It costs him his leg.

Another sergeant is wounded in the face from shrapnel. He’s covered in so much blood it’s indescribable.

It’s a nightmare. The most violent deployment I’ve ever expe‑ rienced.

Before long, the medevac helicopter is inbound. The pilot radios to ask if the field has been cleared.

“There’s no way we can clear it,” I say. “This casualty needs to be evacuated. He will die if you don’t come and get him.”

It’s an extremely tight space, but they land. I carry the staff sergeant to the helicopter with a few other soldiers. He’s barely conscious as we place him on the litter, but he grabs my arm so fiercely out of pain I can feel his fingernails piercing my skin.

In that terrible moment, I pause to look at him. I touch his head softly, hoping with everything in me that he’ll be okay. His remaining leg is just sort of dangling there. There’s no question he’s going to lose it.

The medevac aircraft takes off. I consolidate our remaining forces and begin moving. As we reach the exfil point, I’m devastated — for our wounded, and for the soldiers that remain. But I keep reminding myself that everyone is still alive, and that we did the best we could with what we knew and the resources at our disposal. Combat feels natural to me. And while I don’t enjoy some of what I’ve experienced in battle, there’s nothing like fighting side by side with my soldiers. The most unbelievably magnetic experience is witnessing what sol‑

diers will do to save the lives of their friends.

That’s what motivated me that day in Nejat.

Share this post