We're here! This is free Wednesday, and that means you don't have to pay anything (but you don't get Mondays and Fridays - which are really great).

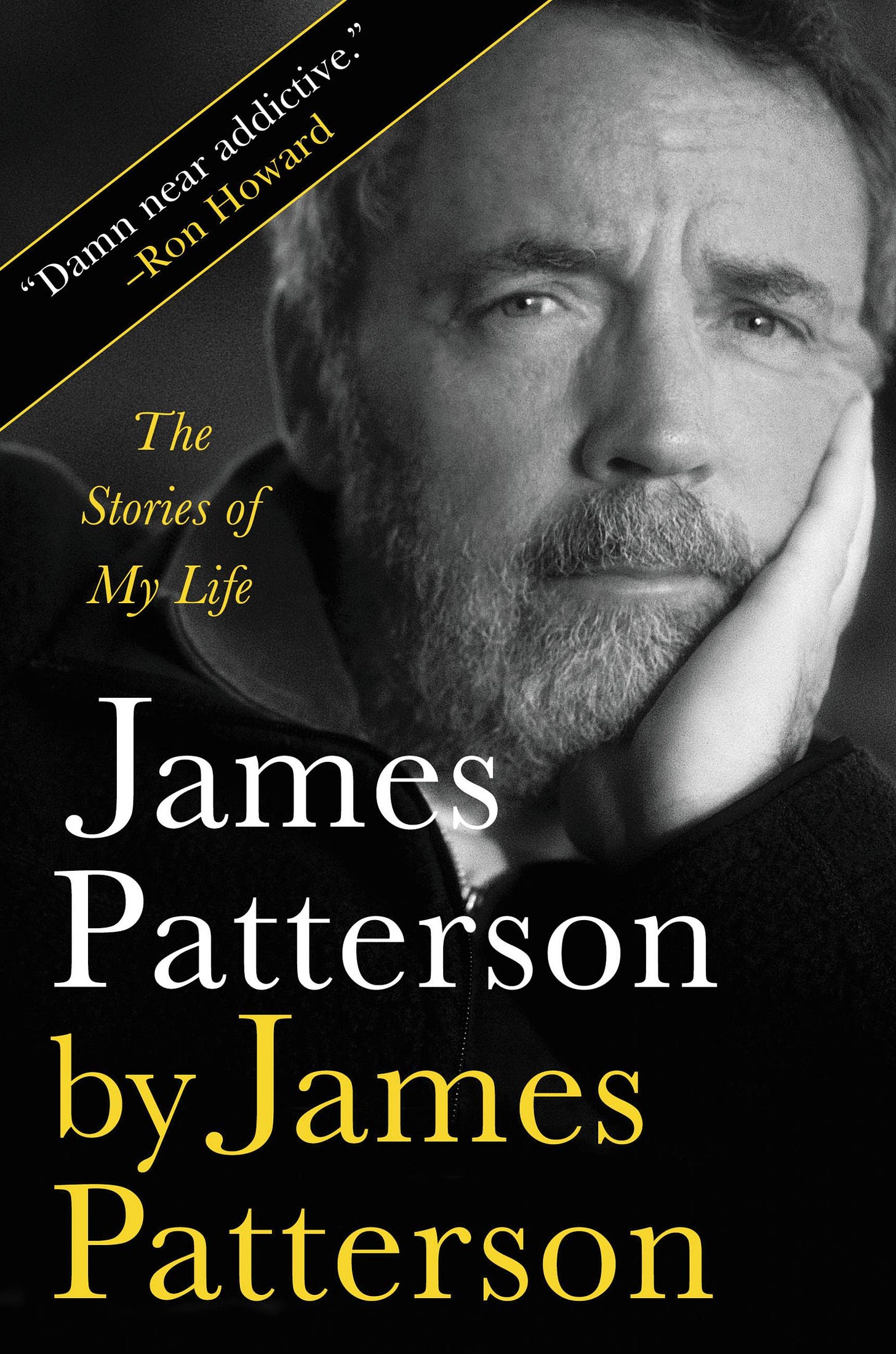

I want to talk about my autobiography, James Patterson by James Patterson, which is the whole title.

I started the autobiography during COVID. I had nothing better to do. So I just started writing story after story. And just to give you kind of a sampling, I worked my way through college at McLean Hospital. I was an aide there, and it was just fascinating. It woke me up. I was sort of a small town kid, and all of a sudden, I'm dealing with a lot of people that had money or, you know, they were crazy in good ways.

And James Taylor, the singer, was there. He wasn't famous yet, and he used to sing in the in the coffee shop, and I could be 15 feet away from him, and he's singing “Sweet Baby James” and and “Fire and Rain” and stuff like that, which he'd already written. So that was exciting and interesting. Robert Lowell, the poet. He came in several times, and there was one other English student who was an aide, and we used to go in there, and Lowell would not just read his poetry to us, but explain what he had in mind.

Early on, when I was 26 or 27, I went to my first sort of literary party in New York City. It was at an agent's house, and there was a lot of noise going on. So I sort of wandered back through this hallway, and there was a bedroom, and it was packed with this sort of literary mob. And in the middle of the room there were these two little men, James Baldwin and Norman Mailer, and they both had their fists clenched and they were arguing about who was a better writer. And I just found it hilarious.

That's one of the reasons I sort of laugh when I think about these various little things that writers get into in terms of who's better, who's worse, or whatever that is. So I learned to smile at that stuff in general. I'd rather laugh than cry at things that happen in the world.

Doing my autobiography at this age - it made me a better writer. It really got me to concentrate more on sentences. Some of you out there, some of you writers, think you're better than I am, and maybe you are, maybe you aren't, but you'll read it as the chapters come along, James Patterson by James Patterson, and you’ll come to your own judgment about your own writing and my writing, and that'll be kind of fun…

See below for FREE chapters from my autobiography, James Patterson by James Patterson.

James Patterson by James Patterson

“The Hamburger Wars”

J. Walter Thompson very aggressively went after the massive Burger King account one year. Burt Manning led the charge. I’ll spare you the gory details, but we won the business — which was always invigorating until we remembered, Now we actually have to do the work and deliver on our ridiculous promises.

The fast-food company was a Pillsbury subsidiary and the billing was almost as large as the rest of the New York office’s put together. Frank Nicolo was picked to run creative on the account. I supervised the adult business, while wordsmith Hal Friedman and a very bright writer named Linda Kaplan were in charge of Burger King’s large kids’ program. (Linda went on to start her own billion-dollar ad agency. Good for Linda. She’s one of my heroes.)

It was Nicolo who must take most of the blame for creating the very creepy Magic Burger King, a red-bearded Tudor-costumed character who, for a brief shining moment, became more popular than Ronald McDonald. That was probably a mistake on our part. We were starting to get under Old McDonald’s skin. More on that soon.

“Aren’t you hungry for Burger King now?” was a campaign that I created. My bad. I called this style of advertising “hard sell that people love to watch.” I know, it makes no sense. But clients seemed to buy it.

The Battle of the Burgers was also one of my creations. In those ads, many of which were penned by Friedman, Burger King got aggressive with Old McDonald’s. Burger King broiled its meat; Old McDonald’s fried theirs. Burger King’s regular hamburger was bigger than Old McDonald’s regular hamburger. Most of the spots were charming and funny, which they needed to be. We were going up against an American icon, a very rich and powerful icon.

For some reason, the whole country took note of these ads. Almost every night, the campaign was featured on the TV evening news. Dan Rather would comment on the latest ads in “the Burger Wars.” He’d show one of our TV spots as part of the newscast. It was even better than free advertising. The story was covered in newspapers and magazines like Time and Newsweek. Of course, this was back in the day when some people actually watched the nightly news on TV and read newspapers and magazines made of paper.

Maybe it was the baseball-themed spots that ran during the Cardinals versus Brewers World Series, but the loftier-than-thou McDonald’s Corporation got so irritated, they filed a lawsuit in federal court. All of the suspect Thompsonites were deposed, but nothing much came of the claims against the taste-test research. I couldn’t help feeling that the whole thing was unnecessary and kind of hilarious. The Battle of the Burgers! C’mon. But I loved goosing Old McDonald’s. To be fair, I enjoy an occasional Quarter Pounder, and I’m a fan of Ronald McDonald House and all the good it does.

Meanwhile, I continued to work on my novels. I’d write early in the morning, every morning. I’d lock my office door at lunchtime and write for half an hour. I’d write on the plane during every business trip. I’d write pages at four in the morning, and I’d write again until midnight. I refused to give up on myself. Though maybe I should have. I finished See How They Run and Black Friday, and both novels were pretty bad. Then I wrote The Midnight Club, which I thought was decent. I hoped I was finally learning from my mistakes.

Then one day I came up with a character I really liked — she was called Alexis Cross. That’s right; when I started writing Along Came a Spider, Alex was a woman.

But I’m getting ahead of myself again. My brain works a lot faster than my pencil.

“The Hellfires Get Even Hotter”

I can describe my success in advertising, and even in publishing, in one off-color paragraph.

When I was the young creative director at Thompson New York, a crafty veteran account man by the name of Bob Norsworthy thought that I was arrogant and full of crap. He wasn’t all wrong. But I kept making the right decisions. And so Norsworthy — a very funny raconteur from Kentucky — came up with the following: “If Jim Patterson says a grasshopper can pull a plow, hitch up that little motherfucker.”

What Bob Norsworthy meant, I think, was that I had a good gut, good instincts for what was going to work and what wasn’t. Is it that simple? Sometimes, I think that it is.

Meanwhile, Advertising Satan continued to use his wiles on me. I was in my mid-thirties when I became the youngest creative director ever at J. Walter New York. Or so they told me.

I was always clear about the work — what was good, what wasn’t. I would always say, “This is just my opinion” — but in the end, I was the person in charge. I didn’t often take the praise, but I always took the blame.

Around this time, I teamed up with Steve Bowen, an ex-Marine who used to keep a grenade on his desk. I don’t think it was an armed grenade, but it sure looked like it. And he thought it made his point, whatever in hell his point was.

That was Steve’s style: macho and Marine, provocative, combative, and, occasionally, a little hard to understand.

Steve had a way of speaking that people in the office came to call “Bowenisms.” He did come out with some unforgettable lines. “There’s got to be a golden pony somewhere in all this horse shit” and “You can’t leap tall buildings with a puckered asshole.” Steve Bowen might have been a distant cousin of my old high-school principal, Brother Leonard.

He was a great partner for me. I tended to be more measured. Somehow our partnership worked oddly well. When he and I took the reins at Thompson New York, the flagship office was seen as stodgy, old J. Walter. We pulled off some loony-tunes-crazy stunts to try and counter the image.

J. Walter Thompson had moved its offices a few blocks north. One night, we commandeered the lobby at 466 Lexington and threw a totally ridiculous WrestleMania event. At least we understood how absurd it was. I did, anyway. Steve — not so much. We invited the entire New York advertising community to come to dowdy J. Walter Thompson to watch live wrestling in the enormous atrium at 466, have some laughs, and party like it was 1999, a decade or so in the future. Most of the agencies came, and they partied, and Thompson’s image changed almost overnight.

When Steve and I took over the New York office, our largest account was health-care and consumer-products giant Warner-Lambert. Less than a week into the job, we were summoned to meet with their COO and president, Mel Goodes. We knew it wasn’t going to be a fun visit to Morris Plains, New Jersey.

Mel turned out to be a good guy, but at that first meeting he told us, “Look, fellas, right now we’ve got three ad agencies — Thompson, Y and R, and Ted Bates. I’m sorry to say this, but I have to rank you guys fourth out of three.”

I told Steve I thought I could not only fix the problem but that I could fix it almost overnight. But it would take some courage from the account managers — the Suits. Steve was on my side, and he was never lacking for courage. The few, the proud, the ex-Marines.

In recent years Thompson had been bringing Warner-Lambert as many as a dozen creative approaches for every assignment, then letting them pick. The Suits were responsible for that strategy. In my opinion, it was suicidal. No agency could create a dozen approaches that had any chance of working in the marketplace. From that day on, we presented only two or three campaigns, and only ones we believed in. Steve and I promised each Warner-Lambert brand manager that we knew the difference. They began to trust us.

Within a year, Mel Goodes invited Steve and me to dinner at the Palm and said we were now his number 1. He picked up the check for dinner (a rarity for clients) and also handed us a bundle of new business.

During the next four years, Bowen and I doubled the size of the New York office — twice. I hated to admit it, but advertising hell was almost starting to be fun. I was beginning to enjoy the constant fires and the blistering heat.

The New York office was thriving. But Thompson was having big troubles elsewhere. Industry analyst Alan J. Gottesman quipped that J. Walter Thompson “[has] problems in places where other companies don’t even have places.”

“Hitch Up That Little Grasshopper”

One big problem with the creative department at J. Walter Thompson was that — when I started running it, at least — nobody very good wanted to work there. I doubted that we could recruit a decent porter. Thompson New York was seen as uptight, stodgy, and not very creative.

How uptight? Back when I was hired, female vice presidents were encouraged to wear hats inside the office, and women weren’t allowed in the executive dining room; instead, waiters in tuxes brought lunch to their offices on trays under silver plate covers. Fortunately, most of that had changed by the time I became creative director, but we still had a ways to go.

Necessity truly is the mother of invention, so here’s what I decided to do about our personnel problems in the 1980s. I ran a full-page ad in the New York Times. Back page of the business section.

The headline got right to the point: “Write If You Want Work.”

What followed in the ad was a test for writers and other creatives. Eight deceptively tricky questions. Here are four of them:

The ingredients listed on the tin of baked beans read: “Beans, Water, Tomatoes, Sugar, Salt, Modified Starch, Vinegar, Spices.” Make it sound mouthwatering. You may have heard this story about the person who made a fortune selling refrigerators to Eskimos. In not more than 100 words, how would you sell a telephone to a Trappist monk who is observing the strict Rule of Silence? (But the monk can nod acceptance at the end.)

Design/draw two posters. One is for legislating strict gun control laws. The other is in support of the NRA.

You just learned that the IRS is planning to lower the percentage ratio of income to medical expenses, thus lowering the tax deductions for dental, psychiatric, and medical expenses. You are a reporter for a daily newspaper. The editor wants to make this a banner story. Write a compelling headline in a coherent two-column story.

The reason I ran the ad was that I was desperate, but I also suspected there were talented people out there who would be great in advertising — they just didn’t know how to get in the front door.

So I made it easy for them. I showed them a side door.

We received a couple thousand submissions and we hired eight writers from that one ad in the New York Times. We then sent the ad and the story around to the media, who proceeded to run our ad for free.

Over the next few years, we hired over fifty writers based on “Write If You Want Work” and a couple of interviews. I could evaluate the test-takers in a couple of minutes and immediately tell (a) whether they could write worth a damn, and (b) whether they could solve problems.

Of the fifty-plus creatives we eventually hired, only one didn’t work out, and that was because he was claustrophobic and couldn’t be in an office.

My favorite hire turned out to be my eventual kids’ book partner and pal Chris Grabenstein. Another good hire, Dan Staley, went on to become a producer on Cheers. Tony Puryear wrote the original screenplay for the hit movie Eraser. Craig Gillespie directed I, Tonya.

Good for all of them.

I have a signed copy and loved reading about the man behind the legend :)