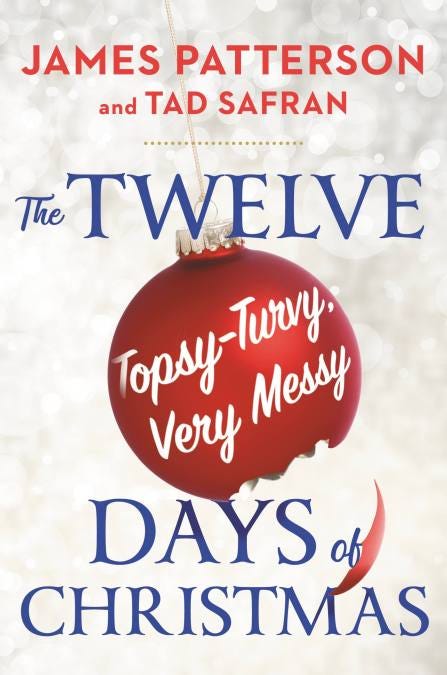

See below for FREE chapters from The Twelve Topsy-Turvy, Very Messy Days of Christmas. PLUS a chance to win free signed copies of the book. Skip the holiday shopping and subscribe to HUNGRY DOGS!

The Twelve Topsy-Turvy, Very Messy Days of Christmas

The Day Before the First Day

Chapter 1

What is the worst present you ever received for Christmas?

A pair of socks?

A pair of scratchy socks in a vile color?

A pair of scratchy socks in a disgusting color that rub your big toes every step you take?

A pair of coarse socks in a foul color that rub your big toes and you’re forced to wear them because your grandmother gave them to you and she’s coming to stay?

That’s pretty bad. But for Will and Ella Sullivan, the worst thing they ever got for Christmas was a dead mother. Apologies for going so dark before the first page is even over. Apologies if, in your shock, you allowed your cookie to plop into your milk. But the simple truth is, people die every day. Statistically speaking, someone unfortunately has to die on Christmas Day. For Will and Ella Sullivan, it was their mother.

So when Christmas rolls around — as it does every year — and all the houses on a particular modestly gentrified Harlem street are festooned with Christmas lights and decorations, one large, decaying Victorian house with chipping paint remains unadorned. This is the house where Will and Ella Sullivan live with their father, Henry. It remains an island of somber darkness that seems to deny the existence of Christmas, fortified by a seasonal gloom against any encroachment of jollity that may try to breach its borders. For at this time of year in the Sullivan house, stockings go unstuffed, tinsel unstrewn, gifts unbought, mistletoe unhung, chestnuts unroasted, carols unplayed, cookies uncooked, and a tree un-visible.

Not only did Will and Ella lose their mother five years ago, they also lost Christmas. (To be absolutely clear, though, they didn’t technically lose their mother. They know exactly where she is. In a tastefully decorated burial plot in the cemetery. At least, she’d better be there because, if she’s not, she’s a zombie or something and these poor children — who have surely suffered enough — risk being subjected to a whole different kind of emotional trauma.)

The house itself is not to blame. It was built in another century — pre-TV and internet, if you can imagine such barbarous times — with adequate rooms and space to absorb the bustle, noises, and smells associated with a busy, vibrant family who had to amuse themselves without the help of Instagram or Netflix.

It was the generous proportions and original features of the house that attracted Henry and Katie Sullivan. It certainly wasn’t the colony of obstinate mice who had taken up residence. Or the peeling wallpaper. Or the pipes that rattled and popped when faucets were turned on. And off. Or the kitchen full of the most modern, space-age, and technically advanced appliances that money could buy . . . during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Despite those negatives, which had chased away all previous sane potential buyers, Henry and Katie Sullivan knew the house was the one for them the moment that they walked in with little Will and Ella toddling around their knees. The task ahead of them was daunting, but they would have a lifetime to fix it up.

Unfortunately, “a lifetime” in this case was to be just four short years.

Without knowing they had so little time, Henry and Katie slowly did what they could afford to do to make the old house a home. Modern plumbing and moderately priced new appliances were a good start. And new paint, rugs, curtains, and comfortable furniture went a long way to brightening up the place.

But the key ingredients were love and laughter. You may not know this, but it’s an accepted fact that no room is completely done until furnished with a child’s giggle. And there was no shortage of those at the Sullivan household.

While Henry was responsible for most of the work on the interior of the house, Katie spent her time outside. Not because she’d forgotten her key or wasn’t house-trained. But because the house had an unusually large walled private garden behind it. Big enough for flower beds, vegetable patches, paths, trees, and a fountain. Big enough for children to play long, exhausting games of tag or even hide-and-seek. This was where Will and Ella’s mother spent her days and her energy, up to her elbows and ankles in soil, turning the overgrown, muddy patch of scrubland into an Eden.

A unique, jazzlike energy and rhythm had surrounded the four Sullivans whenever they were all together, which was almost constantly. But after their mother’s death, that energy and rhythm immediately ground to a halt as the ensemble, over the weeks and months, drifted apart.

Those happy days seemed like a long time ago to Will and Ella, who each now retained a diminishing number of increasingly foggy memories from those laughter-filled years. And Will and Ella, who had once been as thick as thieves, had grown apart . . . Will having grown louder and Ella having grown quieter.

Nowadays, even when they were technically together, they were essentially apart. Mealtimes were quiet affairs with tepid food and conversation, to be endured rather than enjoyed as they had been in the past.

Restaurants, movie theaters, clothing shops, candy stores, and parks — in addition to Christmas — became luxuries for other people and not for the Sullivans. As did hugs, understanding, enthusiasm, and a general interest in one another’s thoughts, dreams, and problems.

Unable to confront his own emotions, Henry was tragically unequipped to understand his children’s. Not that he felt he ever had time to try. He was at his wit’s end just keeping them fed, watered, clothed, healthy, educated, safe, and largely polite.

There were two ways into the garden. A back door allowed access from the kitchen, and a gate allowed entry from the alley that ran alongside the house. Soon after his wife’s death, Henry added a heavy dead bolt to the first and a foreboding padlock to the second. As with so many parts of his life that he had once enjoyed, Henry now ignored the garden. He was too sad to cultivate it himself and too protective to let anyone else. Untended, it soon grew dark and wild, which is nature’s way with almost anything that doesn’t receive the attention it craves.

Chapter 2

The El Grande is a large department store in lower Harlem that has withstood the changing demographics of the local population. One of the reasons for its longevity is its long-standing reputation of offering good value on life’s necessities.

A group of four boys, aged sixteen years old, certainly thought so. They milled about, intent on taking advantage of Christmas bargains. Bargains that the store, however, had not anticipated. Cuz, Bean, Fash, and Noodle had been friends since they met in detention several years ago. They were brought together by a shared love of rule-breaking, baggy clothes, beanie hats, and odd nicknames.

When Cuz entered the store, he was athletic and trim, verging on skinny. But the more he walked around the aisles with his friends, the fatter he seemed to become. Soon his long coat bulged and strained until he resembled a textbook candidate for type 2 diabetes. In fact, he looked a lot like his friend Noodle, who was born weighing an eye-watering fourteen pounds and hadn’t met a morsel of food since then that he didn’t like.

Noticing this unusual group of boys shopping as a pack, a keen-eyed sales assistant made his way toward them. Before he could get there, however, he was spotted by another, younger boy standing on the other side of the department.

This boy was about fourteen years old but smallish for his age. He had a mop of unruly dark-blond hair that he regularly pushed out of his face and keen, darting, light-brown eyes that turned green in certain lights and moods. This boy was Will Sullivan. Pulling his hoodie up over his head, he smiled his trademark mischievous grin and kicked the bottom suitcase in an oversize tower of luggage. The stack promptly toppled over with an almighty crash, taking with it two racks of reasonably priced sunglasses.

The moment they heard the noise and saw that the sales assistant’s attention was diverted, the group of boys knew it was time to get out of there. They ran. And were soon joined by Will.

“Stop them! There! Those boys!” the sales assistant shouted to the security guard, who immediately chased after them. The guard had been a sprinter in high school fifteen years ago. And he was determined not to let the blue polyester uniform pants that clung annoyingly to his thick thighs hamper his thief-catching abilities.

The boys skidded down aisles and through departments. Hot on their heels was the security guard like a lion after a group of gazelles . . . who had stolen from the lion. Running down escalators, they knocked shoppers out of the way until they burst out of the shop and into the bitterly cold New York afternoon as if shot from a cannon.

Cuz reached into his coat and pulled out a couple of T-shirts. He thrust them into Will’s hand and said, “Good job, Will.” The other boys patted Will on the back. Bean gave him a playful punch on the arm, which actually hurt quite a lot, but Will grinned through the pain, happy to be one of the gang. His enjoyment was cut short when the security guard arrived outside of the store and spotted them.

“Everybody split up,” barked Fash.

With that, the gang dispersed in all directions. The last one to go was Will, who was hurriedly trying to unlock his bike from a railing, but his cold, anxious fingers seemed to have a mind of their own. Finally, just as the security guard was reaching out for him, Will whipped his bike away, swung a leg over it, and pedaled away as fast as he could. As he disappeared around the corner, Will looked over his shoulder at the gasping security guard and gave a cheeky little wave.

If he hadn’t turned around to give that unnecessary wave, Will might have seen the pretzel cart right in front of him. As it was, he didn’t and, spotting it only at the very last moment, swerved, pinballing his bike from a wall into a lamppost and down to the ground. Hard.

Will lay there for a moment as pedestrians, muttering at the inconvenience, stepped over and around him. He painfully picked himself up and limped away with his bike, disappearing into the crowds before the security guard could see that his quarry had been injured. Will had luckily escaped with nothing more than a few minor scrapes.

His bike, on the other hand, had not been so fortunate. The frame was bent to such a degree that it looked like it had been specifically designed for cycling around corners. He silently cursed pretzel carts and street vendors as a whole for destroying his sole means of transportation and freedom. This was clearly their fault and not his.

Dragging his crooked bike the rest of the way home through the gritty grayness of Harlem in December, Will grappled with how he might explain the dilapidated state of the bike to his father. But he was soon distracted by pleasanter thoughts. As he passed houses, Will found himself craning his neck to look through their windows. He observed the lush Christmas trees colorfully hung with baubles and tinsel. He saw extravagantly wrapped gifts piled high under trees. He saw long, thick stockings hanging from mantels and smelled the cookies baking in kitchens. He sighed deeply.

WIN THREE SIGNED COPIES OF THE BOOK!

TO WIN:

Subscribe to HUNGRY DOGS at the button below.

Subscribed

Share this post.

Share this post